The Lost Continent

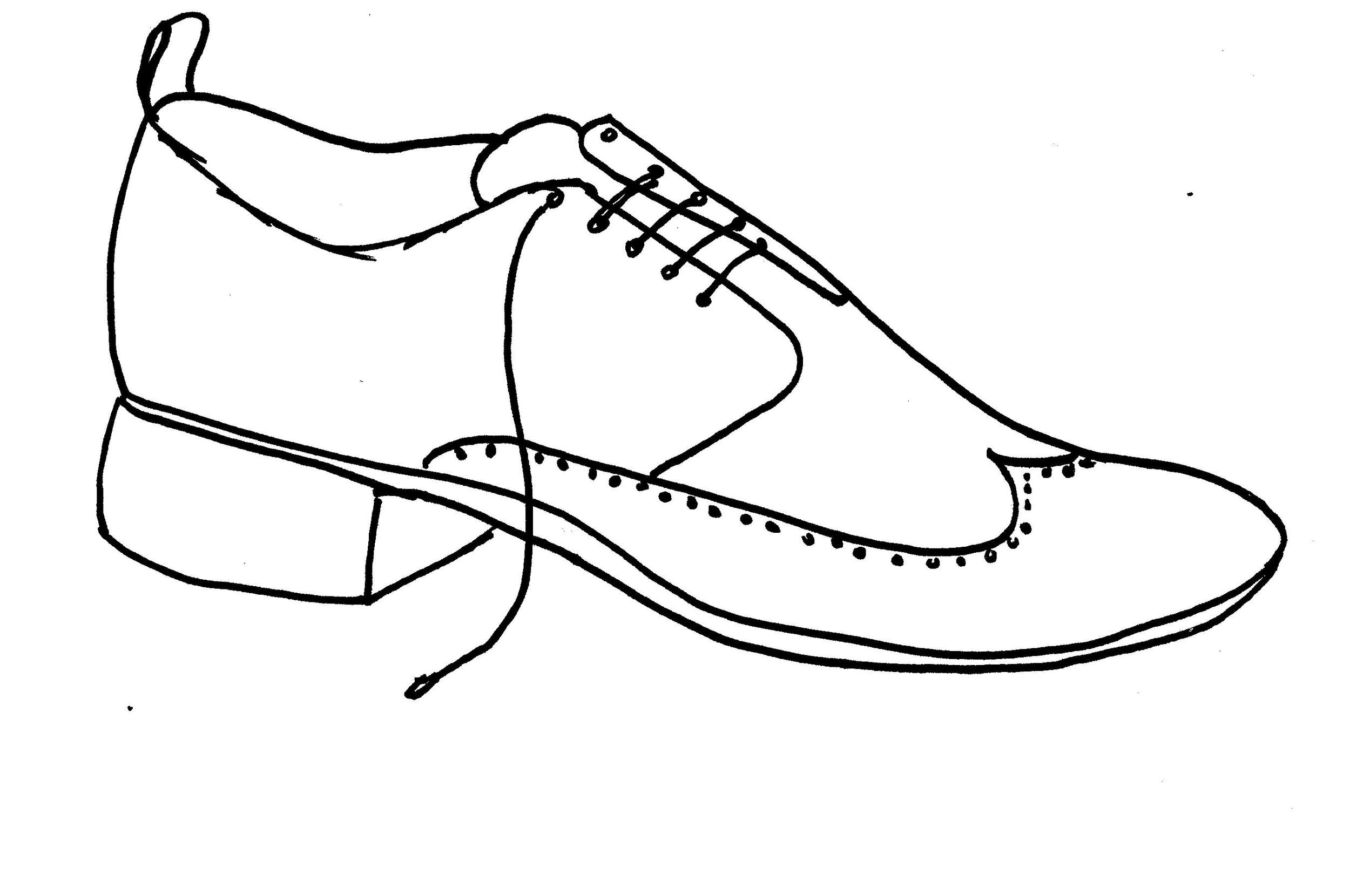

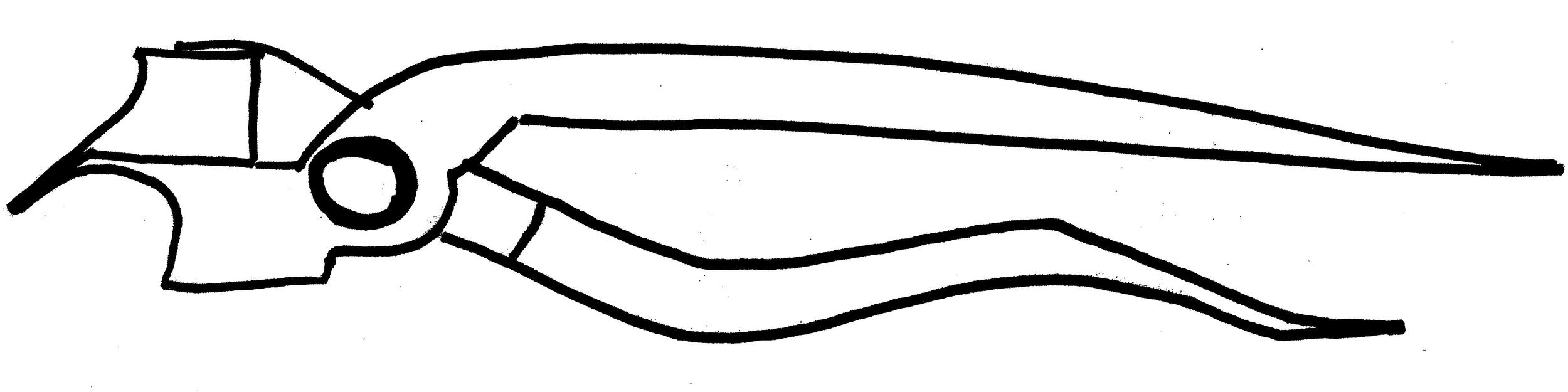

I was sat beside the open window when the letter finally arrived. I had my tools in my lap. They were spread across my knees, pillowed in their rawhide bundle. The compliant, bored and weary instruments of my trade. I was working on the heel of a leather business shoe. It was burnished brown and conservative in nature. I imagined it belonging to some frigid bank-clerk or repressed civil servant. You know the type.

I had meant to finish repairing it in the shop the previous day, but I kept bungling the stiches. Sixty-seven stiches in a shoe, did you know that? We counted them out in our sleep. They were ingrained in our souls. Only ever sixty-seven. You didn’t know that, did you? Now you do.

We had to count. Mistakes came directly out of our end-of-week envelope. Twelve too many stitches and five botched heels resulted in a significantly lighter pay-packet, and could mean the difference between a flush run for your days of freedom or scraping beans from a tin until the following Friday. So you didn’t make mistakes. You quickly learned to work fast and to work well, and life was good sometimes. But with this shoe I kept coming up a stich short or a stich long. My old reflexes were cheating me out of their somnambulant step, relieving my pocket of the secure and comforting weight of possibilities, and robbing my weekend of any sense of purpose beyond my tools and my window sill. And now I was distracting myself by peering out the window across the slate-grey roofs that held up the deep, icy blue sky of a sunny London winter.

When the flap of the letterbox clattered in the hallway to announce the new arrival I acted surprised to myself, but that was a lie. I’ve always been very good at hiding me from me. In some secret cave, huddled away from sight on the leeward side of my mind, I’d always known it was only a matter of time before it came. So I didn’t get up straight away. Instead I sat with the shoe gloved over my left hand and counted out the stiches to spite myself. Careful and slow now, like a novice all over again. One, two, three, four… all the way up to sixty-seven. I looked the shoe over, examining the handiwork. Not my best, but it would pass. To make up for the shoddiness of the needlepoint I took a rag to rub the shoe down and then gave it a polish for good measure. Give a customer back a shiny shoe and you’ve done a good job, in their eyes at least. Presentation is half the battle. It wasn’t a policy I usually stood over but times and needs must. I rewrapped my bundle, putting my tools back to sleep, placing them and the shoe in a tan canvas bag that I used to carry things, my lunch and the newspaper, to and from the shop. Only then did I allow myself to venture out into the hallway.

Glazed light slipped across the floor turning the white floor tiles amber. As I stopped in the hallway to look for the missive, the lazy shaft unfurled a tawny tendril to grab at the toes of my shoes, lapping against the thick rubber rim of my sole. The letter lay flopped face down on the coarse welcome-mat by the base of the front door. It was spot lit in the door’s sunbeams. I picked it up and flipped it over in my work-soiled hands. The envelope was crisp and white, the paper bonded and weighty. The address was written in a flowing blue script. I knew the hand. Of course I did. But I acted surprised to myself out of habit as I traced my darkened finger across the soft braille crenulations of the handwriting, leaving behind a grubby smear of shoeshine and fingerprint. The stamp was post-marked Dublin. Of course it was.

I took the letter back to the open window and sat with it pressed flat between my palms for a little while. I again looked out across the world beyond the sill, the red-brick and dark blue tarmacadam of the lost continent of Kilburn. I found myself taking in all the little details that tend not to register during the normal run of things; a blackbird perched on the edge of a roof poking through the sodden remains in a gutter, the crisp earthen smell of leaves after rain, the sound of an old red estate car’s clanking engine as it struggled up the soft slope of the street, the echoed shouts of young children as they played and fought and played again in some back garden or alleyway. As I sat there I was still trying to convince myself that I didn’t know what was coming next, but I think even the dimmest reaches of my intelligence were beginning to cotton on to the fact that there was no hiding from this. I opened my supplicant palms to stare at the letter’s smudged face. I ran my finger along the edge of the envelope’s lip, but delved instead into the reaches of my memory to look for some sense and some peace and some time.

My name is Mikey. I suppose we should come to that now. I work, as you may have guessed, amongst the roar and rhythm of the bench machines and motors that are part of a cobbler’s trade. I am one of four that still work here, the youngest and eventually to be the last I would imagine. As the factories that made our great machines slowly lose voice and retire into the weeds and rust, so too do the old boys that I call my colleagues. And yes, my friends too sometimes, when life is good.

You could say I was born into this. I mean, I’ve been working a brush since I was ten-years old. I came by it through my old man, himself an architect employed to a firm on Baggot Street. He would shake off his working week in a spray of pints and chatter every Friday night in the pub right next door to Mr. Mullan’s cobbler shop. Please do not misunderstand me, I don’t mean to paint the picture of a drunken cad squandering his week’s wages in a Friday night splurge. He simply carved out a little time for himself in which he was not an architect or an employee, a father or a husband, but merely Joe Byrne. I do not grudge him his little island. None of us did.

It was there that Michael Mullan and himself became friends. This was before my time, and I don’t know if they ever saw each other outside of the shop or the pub, but I often wondered if I hadn’t been named after him. It’s hard to explain, but in the modest and soft-spoken ways of my elders, Michael and my father were strong friends. You could have imagined them dragging each other through mud-drowned trenches in between the smack of explosive and the rattle of earth, only they hadn’t.

When I began to look for a way to earn some money to line my pockets for the week, it just so happened that Mr. Mullan was looking for an extra hand as well. My father suggested that I was willing and able, and that was that. From then on it never really seemed in doubt that I would end up learning the shoe trade. I just seemed to suit the place and it suited me. Dad was not disappointed in my decision. I don’t think so, anyway. But I suppose there’s always been a little part of me that puts his unstated approval more down to his friendship with Mr. Mullan rather than an independent respect for the direction in which I was choosing to point my life. Would it have been different if he’d never met Michael? I'd ask myself that at times when my hands know their business well enough to let my mind free and my eyes loose to look through the walls out into the yellow-hazed distance of the Dublin Mountains. It is a silly question. I know this. But so often we cannot help ourselves.

It doesn’t matter. Really, it doesn’t. I enjoy my work. I use my hands and I make something. I’m good at it. Usually I am, anyway. I enjoy being able to sit back and observe my work once I have finished a piece. It is a simple thing, but I like it. I always have. Though I am not old, nor am I new to this business, and that sense of satisfaction has not dimmed. I think my father knew that. Mr Mullan certainly did. Maybe that is the same thing. Who knows what they discussed?

From the brush I progressed to assistant and then on to apprentice, leaving school at sixteen to learn my trade. The apprenticeship was hard. Completed shoes were passed up from my place down the back of the shop up to Mr. Mullan at the front desk where they were inspected for muster. It was not uncommon for a finished piece to return to my bench by whistling past my ear and slamming into the wall in front of me, clattering accusingly onto my work bench. If the shop was empty a volley of curses would often follow immediately behind the missile. It was all noted and accounted for at the end of the week. Like I said, you learned quickly. And I did. I had been granted a certain flair for this work, such as it is, so I got by and made it as a full tradesman in fair time.

And life settled in to a familiar tread for a little while. I joined the Friday night session in the pub next door, always understanding that for this time alone I was simply another lad and not Mr. Byrne’s son. I still lived at home, giving part of my wage packet to my mother on the silent understanding that while I did so I retained the status of adult above the rest of my siblings. But even after all that, I still had more money than I could possibly spend in good conscience, so I indulged my bad conscience. I regularly found myself in drink. I was young, younger than I am now, and this was almost expected of me. As long as my work did not suffer my evenings went unremarked, and life was good for a time. Then one day I met Sarah Doyle.

Typical? I never said that I wasn’t.

I met her first in the shop. She came in with a pair of black, heeled work shoes for repair. I was looking after the counter that day, so when the bell rang and I emerged from the benches at the back to the front store she was already standing there waiting. Her head was turned away from me, watching the rest of the world pass by the shop’s main window. The shoes were placed in front of her on the counter. When I saw her time did not stop. It was nothing that dramatic. In my experience life works in slower ways than that. Perhaps it is just me, but I have never known the bursting flood of… of what? Love? Feeling? I don’t know. Whatever it is, I’ve never had it. For me it’s always been slow, like a dripping tap that fills a sink in time. I’m not sorry about that. Do not pity me. I prefer it this way. I pity others with their rush and force and panic and thrust. They might get the sensation but they cannot taste the flavour. I get to savour all the little things as they take seed and swell and blossom. I like that. So time did not stop for me, but it did alter. As soon as I’d caught sight of her, with deep brown hair resting on her shoulders in gentle curls and her grey overcoat covering the sky-blue dress underneath, it was like entering a cocoon within which the outside world held no purchase. Life continued on outside and the old men, my colleagues and friends, worked the benches in the back without the slightest notion that a few yards away the entire world had moved beneath my feet. Only a fraction perhaps, but enough for things to have changed.

I stepped up to the counter and her eyes turned to mine. ‘Hello. How can I help you?’, I said.

I was neither fully aware nor completely ignorant of what was happening to me. For her part, she also kept her cool. If her pulse had quickened she did not show it, and in all that occurred between us since meeting in the shop back then and my window-side chair today, in all that we shared, I never sought to ask her about that day. I cannot rightly say why. That moment often surfaced in my thoughts. Maybe I was afraid. I did not want a contradictory perspective to taint the memory and so fear prevented me from asking. I preferred instead to preserve the mystery and sense of possibility that moment contained. Even now I don’t know what she felt truly. I don’t like to dwell on that side of things for too long.

‘Hello’, she replied, pushing her shoes across the counter towards me. ‘I need to get these seen to.’

She kept her hands cupped around the pair until I reached across to accept them, as if they would fall if they were not held. My fingers brushed against hers as I took hold of the shoes and she did not rush to break the contact. Maybe that was why she struck me like she did. Maybe I went back and coloured in the aspect of the early moments to suit this version of the memory. Or what if it was a line of dominoes which, when significantly stacked, would come crashing together to create a solid and curving line between that and this. You choose. It’s all of these things and none of them. If ever there was a secret to life then there it is. You can take that on my authority if you wish.

I took up the shoes one at a time and turned them over in my blackened hands to inspect the work needed and the likely price.

‘They’ll need to be re-soled and re-heeled. With a little bit of stitching too.’ I scratched out the price on a yellow docket. ‘Can I get your name?’, I asked without looking up.

A silence drew out while I waited for an answer. I looked up and met her eyes again. They were calm and green. Her face was smooth of any expression as she let the distance from my breath to hers fill with swirling drifts of dusts illuminated by the sunlight spilling through the shop window. She looked young and beautiful.

I began to flounder for something to say but as soon as I uttered a sound a warm grin bloomed across her face. She smiled not just with her mouth but with her entire face. Eyes, ears, forehead. Everything.

‘I’m only messing with you. My name is Sarah Doyle.’

‘Yes’, was all I could manage in reply.

I imagined her eyes on me as I pointed my reddening cheeks towards completing the docket. A few more moments of silence passed between us with only the sound of my scribbling to fill them in.

I finally picked it up, tore off the carbon and passed it over to her. ‘It’ll take about a day, maybe. If you’d like to call in again on Thursday.’

She gripped one end of the docket but did not pull away from my grasp. ‘I’m working all day Thursday but I’ll drop in on Friday morning to collect them, if that’s okay?’

‘No problem at all.’

I let the docket go just as she pulled it away. She slipped it into the pocket of her overcoat, her hand creating a hollow bump in the fabric as she withdrew. She smoothed out the creases with her palm before stepping back from the counter.

‘I’ll see you later then’, she said.

She turned and left, opening the door to re-join the world. And just like that, our small cocoon was breached. The rest of the world came rushing back in again - the smell of leather and polish, the clack of the machinery, the gurgling radio, the passing cars outside. I watched her go. She did not look back and smile over her shoulder, or sneak a glance as she passed by the window. No. Nothing like that. She simply planted her gaze on the ground beneath her feet and tucked her hands into her overcoat pockets as she moved away out of sight. I had no doubt she would smooth out the pocket creases again when she reached her next destination. It made me feel good to know a little part of her like that.

Can you guess the story from there? I’m thinking you can. Some of it, anyway. Or at least something very like it that makes little difference.

Friday came with Mr. Mullan back working the counter. When Sarah came in, I engineered some reason to emerge from the back, passing a greeting with her as I pretended to stack some shelves of shoes waiting for collection. She played her part, contriving to drop into conversation with Mr. Mullan where she was like to be found of a Saturday night. This was a blessing in a way as I didn’t rightly know how to avoid Fridays in the pub next door.

The following day I trekked out to some dance hall hidden deep in the Liberties. I managed to find her, exchanging a few words between a phalanx of friends with crossed arms and pointed shoulders. Next Saturday I got a dance. The following Saturday I got every dance. The one after that I strolled her home down along the canal. And then? And then a kiss. Just a kiss. Short but warm, urgent and hungry beneath the eaves of a willow tree that spread its shelter out across the water. We were surrounded by the smell of bark and earth, and as we kissed I rested my hands on her hips while she placed her palm against my cheek.

You know the rest. You do. You do. I know that you do. That is not for me to tell here. That is not for you to know in full. We can skip all that. Fill it in yourself.

The next thing you need to hear about is Stephen’s Night and Larry Fuller’s dance.

For those of you that understand, and I reckon that quite a few of you do, Stephen’s Night is the night. The night. They call it Boxing Day here. I didn’t know that when I first came. It’s not the same. Here it’s all striped football scarves and tight closing times. ‘Time Gentlemen, please.’ It’s something else altogether at home. At home, after the leftovers, after the relatives and visits, after the mass, it’s the one night where everyone is on the off. Perhaps it is because of where it lies in the calendar, in a little cul-de-sac at the end of the annum. The year gone is now properly done but the year ahead has not yet come to dominate thoughts, actions, plans and resolutions as it does at New Year. On Stephen’s Night you don’t reflect and you don’t look forward. Everyone is just present. Everyone. The entire country gets locked in and for the length of one shadowed evening, life’s sharp wind is gentled, laid calm, and the people claim back the hours for their own. For some, it is in a public house, packed and pulsing. For others, it is by a homeside hearth that is warm and secret. For us, it was in the fields of Kilmainham.

Back in a time when the city was darker than it is now, and its reach could not stretch beyond the cloistered frown of Christchurch, the fields of Kilmainham, in what now houses the Royal Hospital, once held infamy for hosting the illicit and drunken revelry of the city. Hundreds would gather there on the edge and toast a life that was older and less fickle than the societal graces that glowed dimly in the distance.

Mickey Mullan had told me all of this one day in the shop after overhearing me mention Larry Fuller to one of the boys. He shined a boot as he told me the history, never mentioning Larry or his activities. However, once he exhausted his knowledge on the subject he fixed me with a look that leaped over the top of his half-rimmed glasses, a look that told me with no uncertainty that he knew exactly where I was headed, with whom, what was on offer out there should I be so foolish, and what he thought about all of that.

You see, Larry Fuller had resurrected the ancient rites of revelry out there on the cold grounds of the hospital in a fashion that was not entirely approved of. Not approved of because it was unsupervised, unsanctioned and full of young people. But what can the old do about that? Mr. Mullan knew enough to recognise that a guiding hand was better than a blocking one, but even so.

The organisation was nothing more complicated than Larry Fuller parking himself in a shaded corner of the grounds, far from sight of the main buildings, with a couple of barrels of porter and a few bottles of whiskey. Not a lot, but enough to get everybody started. We brought the rest. Larry was also on friendly terms with Nightwatchmen on the grounds, paying for the privilege of a blind eye so long as the fun was contained within the walls of Bully’s Acre. He would charge a shilling for entry, attracting more than enough people to make it worth his while. The crowd brought their own cups, bottles and instruments, and from about elven o’clock onwards it became the beating heart of the city, or of our city at least.

I had met Larry in a pub on one night or the other, learning about the Stephen’s Night shindig from him not long after. I had attended it with Larry the previous year. Sarah had never been. It was an opportunity to charm her with my inside understanding of the hushed and whispered workings of Dublin. But there was more to it than just bravado; it provided a chance for us to be alone. Alone amongst strangers, perhaps, but there a special kind of deliciousness in the anonymity that strangers provide. You must understand that for all the dances we attended, or the nights we had about town, we were never really alone, not properly. Sometimes it was her friends, sometimes mine, whoever it was there was always somebody in attendance. Our only time truly together came during our walks home along the canal, but these were limited by their very nature and I wanted more. I wanted back into that cocoon where there was just the two of us. The world could continue on its business around us without caring or requiring attention. Larry Fuller’s dance provided this chance, a sea of amiable anonymity and I was anxious for it.

That night I met her beneath the willow and we strolled across the city. The night was crisp enough to redden the tips of our ears and send our breath pluming in front of us like spears cascading out against the cold. She was beautiful, her scarf hemming in around her jawline which caused her to stoop forward just a little as she walked in order to see her way forward. She wrapped her two arms around mine and held onto me as we ambled. It made me feel warm and strong but jittery and nervous too. That night, I cannot rightly explain it, it felt more real, as if the world was just a little more in focus than normal. I knew then, as I have not known since, that anything was possible. If I had but turned my mind towards it, the very treasures of the deep seas could have been mine. The cogs and wheels of the earthly machine were greased and turning smoothly. And they did so for me. They did so for us.

It took us about forty minutes to get to get to Kilmainham, passing home windows with low-lit glows and pubs that thronged against their mortal limits. We talked and laughed as we kept gentle pace with each other. At the grounds of the Royal Hospital we had to scale an old wall that reached just above our heads. I could see the doubt rise in Sarah’s face as I explained the procedure to her. I extended my hand to boost her up. She looked at it, for just a fizzing moment perhaps, but enough to notice, before she nodded and took it up in hers, deciding to place her trust in me. If there was ever one moment more than any other where I realised that I was in love, it was that one.

There, I’ve said it. Are you happy now? I told you I was typical.

She stepped into my palms and I lifted her up onto the wall. She in turn helped me scramble up. I hopped down the other side and guided her down. The grounds were dark but I knew where to go and it wasn’t long before we picked up the thin strains of music and chatter, following them into the shadows of Bully’s Acre that crowded beneath the trees.

Bully’s Acre was a walled field that had once served as a cemetery. Old gravestones found themselves leaning against large tree trunks that dappled the field and lay a roof of branch and leaf over the field’s full expanse. The grass crunched beneath our feet and people were spread out in groups and couples across the acre. An open session of fiddle, guitar and drum held court in one corner and many people spiralled and spun in a small clearing in front of the musicians. This was the dance from which the evening gained its name.

What to tell you about the night itself? You can never do those things justice with mere hindsight. It was a fantastical thing to cast your eyes out across the moon dappled field and see hidden peoples emerge from beneath blanketed shadows to dance and laugh and sing their way between stone sentinels and huge pillars of wood that held the leafy sky aloft. And all the while, through all that time, right beside me with her gloved fingers woven together in mine was Sarah. I could look at her and know that for tonight she was there with me and me alone.

The night took flight and people drank as if they were throwing fuel into the fire, with every sip and slug guiding us a few feet higher, every jig and reel propelling us up on a new current of air until the amber drenched city looked small beneath our feet. Those nights do not crash to an end, they reach a crest and then glide back down so slowly that you barely even notice.

At some point a fire had been lit, I didn’t know when. A few people had left and the music has shed its desperate triumph in favour of a sound that drifted across the field and placed a soothing hand down upon the restless and riled. Myself and Sarah had retreated to a hollowed corner that met at the join of two stone walls and had a pair of hunched trees guarding it. We lay down in our secret crater and were lost to sight from the remainder of the crowd. The flicker of firelight and occasional trill of laughter spilled over the hollow’s lip to remind us that people still moved but making us seem so much more removed from them as we basked in each other’s company.

The ground was cold so I lay on my back and she rested her chin on the rise and fall of my chest, her body draped over mine. The pressure of contact was hot with the spark of our beating hearts and edged with the nervous pulse of our bodies. The way she peered into my eyes, her hand balled in the basin of my neck and her hair swept back and quiffed, made her look almost feline. I felt claimed. I felt wanted. Needed, even. It melted through the ground. I did not feel the cold.

‘I want in’, she said. ‘I want you to let me in.’

I hear that whisper now when the clack of the hammer echoes in the workshops, when I scrape my way down sodden city pavements, when I sit in this chair and look out over the rooftops. I know I will hear it years from now when I greet the ground again. I want in. I want you to let me in. A soft tapping on my soul. I want in.

I didn’t know what to say so I reached up and we kissed each other with open, watching eyes. We kissed long and deep and searching, almost desperate.

Our lips parted and her gaze dropped from mine and her chin returned to its place on my chest. She wanted more, I could see that, I’m not a complete fool, but I didn’t have more to give or if I did, I did not know how. She took to fiddling with the lapels of my winter coat, picking off bits of lint that weren’t there, like she was embarrassed or exposed. The world about us was still except for the firelight’s slow murmur of serious conversation, yet I could feel that life was in full flight and that something was rushing past me that would soon be gone.

I fumbled for something to say, anything, reaching out to grasp what I could. I came away with only, ‘Did you enjoy the night?’

Weak. Feeble. Frayed.

I do not remember her reply.

When the sun finally came up it found our sacred hollow empty and the rest of Bully’s Acre returned to its long-term residents. All traces of activity removed except for a small smouldering circle of ash.

I cannot rightly explain what happened next, or why. That's unhelpful, I realise. All I can say is that she had given me something intricate and delicate to hold in my hands, but in doing so she had conjured a fundamental shift causing the entire aspect of our world together to morph into something else. I had been brought to a turning point that I was not ready for and could not cast my imagination beyond. I felt a basic question had been asked of me and in my failure to respond, I had also failed this simple but essential test. It’s petty and stupid, but slowly this feeling of failure distilled into a resentment for ever having been asked in the first place. I was angry at her. I was angry at the gall of the demand. I was angry that I should be expected to react to such things with no preparation or forewarning. Angry that it was I who was in the wrong for having answered incorrectly.

I was seized by a young child’s passionate urge to destroy. An urge born from the simple need to see if I could. To distance myself from the site of my shame and remorse. And that’s exactly what I did.

It happened slowly. I told you that things happen slowly for me. You don’t need the details. I became cold. I withdrew my affection. I showed less interest in her corner of the world. I saw her on a few occasions after Bully’s Acre but it was forced and awkward. It was as if she were sat in a rowboat while I was on the shore. I simply placed my foot on the bow, pushed her off into the water and watched as she was taken by the current, her face drifting away into the distance.

When I finally stopped seeing her, it occurred with such little fanfare or drama that it was only some time later that I realised that things were definitely over.

Telling this now, I admit that I remember the feelings. I remember the reasonings of the time. But I no longer understand them.

After that home was no longer home. I cannot say I knew this directly. I didn’t. I returned to my previous patterns, of course I did, but the old routines were like a picture set out in the sun and bleached over time. Dublin had lost its colour and possibility for me. Everything had changed. I traced the same sense of failure in every exchange between myself and my father or Mr. Mullan. As if they knew. As if the world was privy to my inability to answer Sarah’s request. I found myself on the outside, looking in on the life I had been leading. The bar-side jokes that were lobbed into the middle of a guffawing assembly were now at my expense, tinged with a bite I could feel but could not quite pin down and say, ‘This, this is it!’

All nonsense, of course. It’s so stupid looking back. But it’s in my nature to hide. I told you this straight up from the start.

I developed a longing to leave. No, more than that. A need. More and more I would cast my mind to the imagined lands beyond Dublin’s horizon and find myself living there in fullness and satisfaction. And happy. Always happy.

What to say between then and now? I frequently find myself attempting to skip bits of the story. I apologise. It’s a bad habit, I know. You can’t ever tell everything. It’s simply not possible in my experience. If you try to include it all there ends up being so much to say that it becomes jumbled and contradictory in the telling. So, I sit with this missive in my lap and skim the possibilities of its content before I finally relent, open it up and seal its meaning to the fixing post. I find that the hardest part, to give up on possibility.

I am nervous now. There is an empty feeling in my chest that is coupled with the rapid pace of my heart. It fuels this engine of change. I swallow and close my eyes as an evening chill darts in through the open window, steeling the keen edge of my nerves, revving this engine harder and faster and with more violence. I don’t want to know what’s inside unless its hope. I know it isn’t. I know it can’t be, and this is what stays my hand. Why should it? I have done nothing, displayed no signal, employed no action that would reveal my desire for hope. If you’d asked me before this letter had arrived I don’t think I could have even told you that I dared to hope. I didn’t know, not until this letter flopped through my letterbox and landed with the leaden weight of inevitability. I recognise her hand. She did not have my address. I think of her stood in the centre of Mr. Mullan’s shop with that same grey overcoat, hands clasped together or maybe with a pair of shoes gripped in them to provide her with an excuse. Then some casual remark or off-hand comment. An address scribbled onto to the torn corner of a docket and slid across the rough, wooden counter top like it meant nothing, like it wasn’t drenched and limp with disappointment and regret and desperation and hope. She picks it up and slips it into her coat pocket, smoothing out the creases just like that time before, once again leaving without looking back. Mr. Mullan’s raised eyebrow as she left, which means my father knows, which means my mother knows.

And from my chair I worry about the imagined lands I left behind, perhaps rashly, perhaps without thought, perhaps from fear. I sit and worry that the people who chose to forget have condemned themselves to remember. I press the letter to my lips and close my eyes again. Below my open window the streets of Kilburn cast shadows across the evening and people move on, oblivious to my precipice over the world and the lost dominion of hope.

Written by Adam O'Keeffe ©2015

Illustrations by Sinead Fox ©2015

READ THE INTERVIEW... Currans of Baggotrath Pl. by Sinead Fox

SEE THE PHOTOS - Click here for the Gallery

NEXT UP - The Stores of The Natural History Museum / Monday 4th of May, 2015

These stories are inspired by, but in no way based on, the things we've been told. We want to make that clear. Anything contained within these pieces of fiction are just that, fiction. In here you will find tales of rich men, poor men, beggar men and thieves. None of them are real but all of them are alive