Costume Department of The Abbey Theatre

It’s the opening night of a new play and the curtains are about to go up. You sit in the hazy darkness of the auditorium amongst wine-soaked theatre-goers, all waiting with anticipation for the show to begin. The world outside starts to fade away. You have no concerns and wait merely in the hope that you will be moved, provoked, at the very least entertained by what will unfold before you. If you are seated in The Abbey, the national theatre, at least one among you however is wracked with nerves and waiting with trepidation for that first show to begin.

“I always feel nervous on opening night, super nervous if it's my own show … but even if it's not my own show, I feel nervous for everybody on opening night.”

Niamh Lunny, head of costume at The Abbey, tells us she feels anxious for the actors, the crew, and for everyone in her own department who has worked on the show in the weeks before that first night.

When we meet her in the middle of the day in the offices of the theatre, it’s hard to imagine her being nervous about anything. She first came to The Abbey as a designer in 2004 and has been there ever since, becoming head of the department in 2007. Clad in skinny jeans, a T-shirt and blazer, her sparkly runners draw the eye as we constantly trail at her heels, weaving through narrow corridors and flights of stairs.

The department has a diverse remit between looking after the costumes for the play currently on stage (always the priority) and then designing sourcing, and prepping for the upcoming show. Such a balancing act means the costume department in the theatre is open 14 hours a day, 6 days a week.

Niamh Lunny

We pass a room with hefty open-top washing machines and Niamh leads us through an office and up a few steps to a slice of a room with large windows where fine artist Sandra Gibney works. A character’s outfit - whatever it may be - of course needs to look like part of the character and not something fresh from a sewing machine or out of a shop. Sandra “breaks down” garments to make them look a particular way.

Taking a jacket as an example, Niamh describes what Sandra might do to achieve this, “She might fill the pockets with stones, pop it on a mannequin, soak it, the weight of the stones starts dragging the whole thing down. And then she'll start working into it with paint to make it look worn and dirty and old. She might get a cheese grater and grate the collar. If she had a lot of them to do, she might actually take out the industrial sander and just start sanding them.”

It sounds weirdly satisfying.

Niamh calls out to Sandra across the room, “I’m telling you … you love it Sandra, don’t you?”

Sandra: “Oh God, it’s like therapy”.

More than wanton destruction though, Sandra uses paint, fabric, shoe and leather dyes and an array of ever-evolving tricks to achieve what they need for each individual piece of clothing.

Walkway to the cutting room

Back in the corridor, we pass a small room stacked either side with rolls and rolls of fabric. Niamh tells us that while they do buy some fabric in Dublin, limited options mean they source from a company in Germany who they’ve worked with for years, and sometimes travel to London and Paris also. We make our way up to what must surely be the top of the building now. After another narrow walkway lined with rails of clothes, we’re into a corner room with large windows - the cutting room - which is flooded with light.

For each new play, the designer gets to work on imagining the costumes after reading the script. “You start looking at the individual characters, the time frame, the time period.” Collaboration is key and talks follow with other members of the team such as the director and set designer. “You’d always try and meet your lighting designer as well to make friends with them - that's the really critical relationship.”

One of the first things that happens is a trip out to The Abbey’s costume hire warehouse in Finglas to find anything that could be useful. In 2009, a restructuring plan was announced at the theatre due to significant funding cuts. In a bid to save costume jobs, Niamh and the department put together a proposal for a costume hire business. They asked for 6 months to get it up and running and it’s grown year on year since, becoming an important resource for theatre and film companies across the country.

“I think one of my proudest moments out of the whole thing was when we got feedback from an amateur company who said that the costume park opening had completely changed the spectrum of work they would do.”

**** **** ****

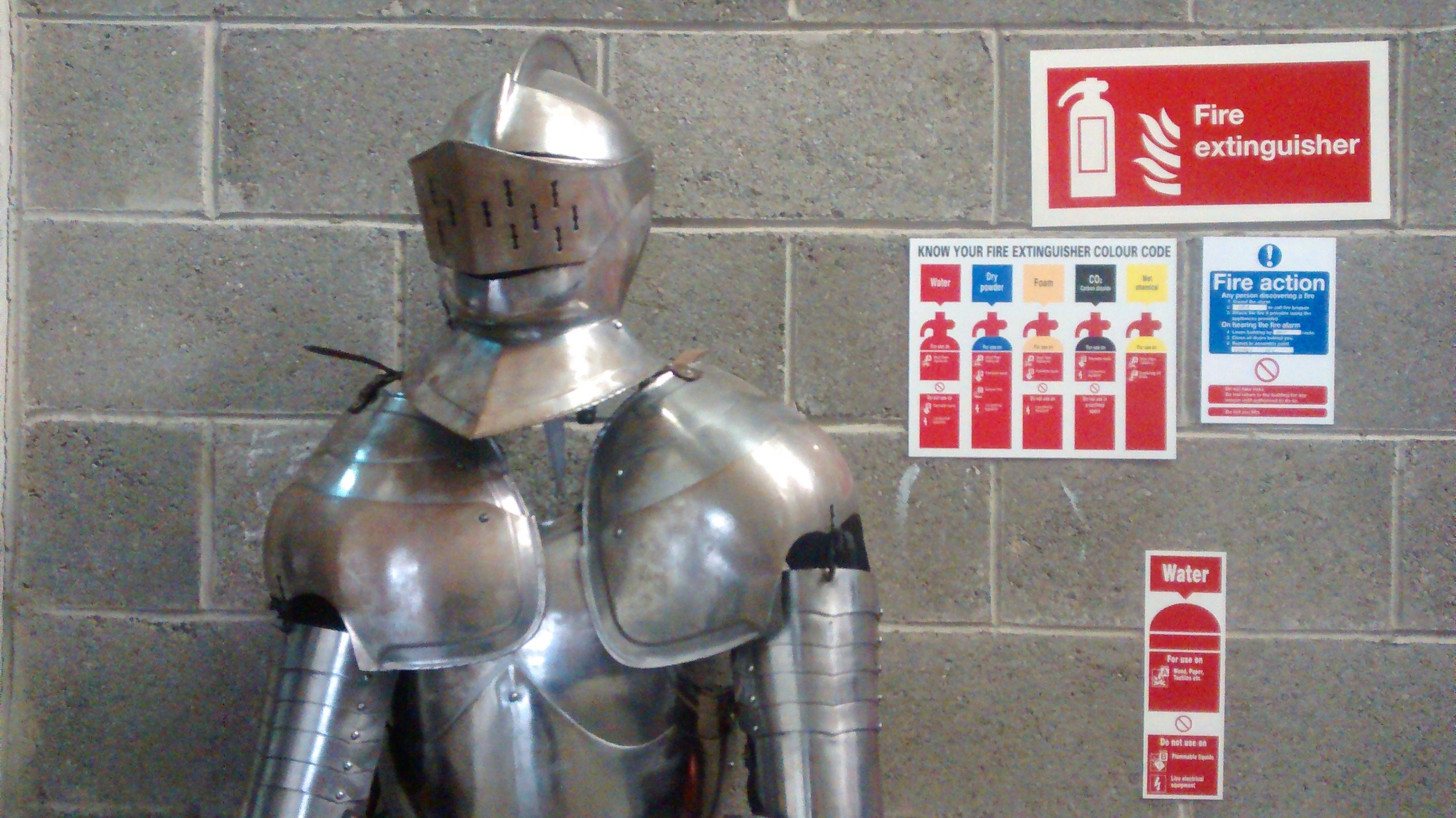

A few weeks later, we head out to visit the premises in Finglas. The first thing that strikes you about the whole place is the contrast. A warehouse in suburban Dublin from the outside looks as non-descript and grim as a you would expect warehouse in suburban Dublin to be but when you step inside everything is not as it seems. One of the first things you pass is a floor-length, deep royal-blue fur coat and hat perched on top of a mannequin – a gift given to the former director Fiach Mac Conghail. An intricate lace wedding dress hangs above a waiting area with a patterned sofa and table. A full suit of armour stands in the corner. Rails and rails of clothes, immaculately organized, hang from the ceiling to the floor beyond it. Saileóg O’Halloran, the costume hire coordinator welcomes us in.

An aisle in the costume hire warehouse in Finglas

Start to walk the aisles and you’ll invariable see rows of Aran sweaters, leather jackets, dress pants, coats, voluminous petticoats – sometimes grouped by colour, sometimes by era, sometimes by style. It is a meticulously neat visual catalogue. The rails continue upstairs and the business is set to expand into the warehouse next door in 2017, such is the level of increasing stock and demand. The warehouse is designed to be as accessible to as many group as possible and everyone – from amateur drama groups to big budget film companies – are treated the same and charged the same prices. (Every item is priced individually and you're looking at a very reasonable €10 for a pair of trousers, €35 for a three-piece suit, or €40 for a period dress.)

As you walk around, certain garments stand out. There are whole swathes of army uniforms of every era and, as you’d imagine, 2016 was something of a bumper year for the business as the Easter Rising Centenary celebrations prompted productions across the country. Saileóg and the staff even went to Collins Barracks and spoke to the military archive curators to see what the uniforms of that time would’ve looked like before creating their own. Working there seems to be something of a history lesson in itself.

“What we notice here big-time is that there's a centenary for everything every year. So, 2014 was 1914 and World War One, 2015 was 1915 which was Napoleonic wars apparently … but because 2016 was 1916 all the films were made in 2015 so we've been in 1916 land since 2013.”

Selection of army jackets in the warehouse

Outside of history, they notice other trends such as the constant demand for Priest’s attire. “That's a big thing for us. They go in and out all the time, you would not believe how many..."

Other frequently hired items include old Garda uniforms, monks’ robes, Orange Order sashes, prison uniforms, military wear, and period nightwear. It’s hard to resist conjuring a picture of the Irish psyche from such items and what they might represent on stage, what they might be collectively saying about us. There’s more than a hint of Toy Story imaginings with certain items, as if peeping out from all these rails in an warehouse in Finglas, they are just waiting for their moment under the stage lights. Occasionally, when you turn a corner and find yourself alongside something as innocuous as a row of pink cardigans, it can suddenly feel as if they were just having a damning conversation about you after Mass on a Sunday. Everyone who has ever lived in your town can be found here.

That sense of dormant magic in these inanimate objects is heightened even more when Saileóg takes us upstairs to the small room at the front of the building that holds most of their accessories stock. Saileóg seems to have the most affection for this space and its contents. A freelance designer herself, she originally studied fashion but also had a love for theatre and became involved with Macnas before coming to The Abbey. She works alongside Kerri Morris and Ailbhe Kelly-Miller who also design, make, assist and dress on a freelance basis too. It’s not surprising to hear Saileóg say that their work in costume hire feeds into everything else that they do.

Suit of armour in the warehouse

Everything in the warehouse is meticulously logged each time it enters and leaves the warehouse. Nothing is computerised and Saileóg instead describes it as being "mind-catalogued". They have an encyclopedic knowledge of what she estimates to be the over 20,000 items that are housed there.

" So ... if people want a tutu we know we don't have it, or if they want a purple tailcoat, we know we have two."

As we maneuver around the room, she points out an array of canes, parasols, trilbies, fedoras, belts, a motorbike helmet, and a very beautiful wooden face made by the set designer and artist Andrew Clancy for a production of Oedipus. The things up here can be just as important, Saileóg tells us, as the garments downstairs in creating the costumes for a character.

**** **** ****

Back in The Abbey, the din of the LUAS roadworks outside provides background noise as sunlight pours through the windows. We meet Marian Kelly, who has been a pattern cutter at the theatre for the last 12 years. Coincidentally, it’s her last day before she takes a career break.

Niamh: “I have to say Marian is the most amazing cutter ever, she's probably the best person at her job in Ireland, [but] she wouldn't want me saying that.”

Moodboard in the cutting room

It sounds like they’ve had a morning of reminiscing and sharing anecdotes. On favourite shows, if they really had to choose – Marian says a production of The Crucible from a few years ago would be hers, “I just thought everything about it [was] just so beautiful, [it] was like a painting.” For Niamh, it would be Marina Carr’s Woman and Scarecrow from 2007. “That had such a profound impact on me, [I] couldn't believe that level of storytelling was possible in the live form.” Interestingly, the same designer, Conor Murphy, was responsible for both.

I ask if they can recall any costume-related disasters and while not a disaster, one story stands out. During rehearsals a few years ago, an actor who was on his tenth or eleventh take of a scene arrived on stage on cue, only to declare in frustration, “I can’t dance in these gloves”. There was also someone else who had trouble playing the piano in their hat, which for some reason doesn’t have quite the same comedic absurdity to it. Humour aside, it probably says something about the strange relationship we all have with our clothes – how our consciousness can be unknowingly intertwined with what we’re wearing and how all of that must be heightened tenfold when you have to stand up on stage in front of an audience. The gloves statement has become something of a catchphrase in the costume department, albeit one with no malice intended.

Marian Kelly at work in the cutting room

Niamh: “Nerves are a part of the job for an actor and part of our job is to help with that and to accept that and to not be making that worse than it is. So, quite often costume can become a focus, if something isn't quite right or if an actor's nervous it can become a focus for that and sometimes it's justified, and sometimes it's just because they're nervous - but whatever the reason we have to just accept that and try and fix it.”

Working with actors is of course an important relationship for the costume department. When I ask what it takes for a show to succeed, both Niamh and Marian agree that collective effort and a team approach is integral. As Niamh says, “It's an openness and a willingness to collaborate, and actually a lack of preciousness and a lack of ego. It's all those things, and on all our parts.”

The rehearsal room - a bright spacious room with one side entirely mirrored - is right next door to the cutting room and Marian and Niamh say they can hear the story start to take shape through the wall. The actors then come into the cutting room to have fittings, a process which they both describe in effusive terms.

Niamh: “[Actors] are fascinating, intelligent, really rounded human beings with enormous life experience who also have so much to tell you, and so much that you can learn from … You’ll hear all about their take on the character, where they think the character's coming from, what they think should be expressed, how they think that should be expressed, and then everything else in between.”

Marian: “You feel you're so close to them, reaching the person they're trying to emulate. It really is a pleasure.”

Niamh in the cutting room

So, it’s not surprising that they all often become unwittingly absorbed by whatever they’re all working on and sometimes even end up dressing like they’re in the show. Niamh elaborates, “We won't have noticed until one day we look around and go ‘Oh my God everybody's wearing a lace blouse today’”, amidst laughter.

The whole process sounds all-consuming and fiercely intimate and of course you’re reminded that it is, both physically and emotionally. It probably goes some way in explaining why the cutting room vaguely feels like the art room in school – it had the best light, the teacher allowed you to have the radio on, and confidences were quietly shared about first boyfriends while you all simultaneously tried to decide the best way to crack your batik. Casual but vital all at once, the room feels like a place full of calm yet urgent work.

Clothing similarly has that duality about it – something seemingly inconsequential yet crucial. In a play, it’s another important element that contributes to the character, the story and how each is communicated. But, like good lighting or set design, good costumes often become an intricate part of a thing that absorbs you so much that all you do is feel what the collective effort conjures up. The costumes become almost hidden in plain sight. In fact, you probably wouldn’t even notice if an actor’s gloves were too tight. But next time you’re in the theatre, spare a thought for any nervous members of the costume department who may be seated in the audience. They’ve worked hard to make sure that all the actors can dance in their gloves.

Written by Sinéad Fox ©2016

Photos by Adam O'Keeffe ©2016